Review & Photography by Manny Manson for MPM

It was one of those nights where the rain outside felt like it was trying to wash Wolverhampton off the map, but inside KK’s Steel Mill the storm was already brewing in a different form. The room was thick with anticipation, an intimate but partisan crowd pressing close to the stage, jackets dripping, some with drinks in hand, ready for noise, the grit and the fire.

The lights dimmed, smoke bled across the stage, and into that haze walked CJ Wildheart, the grin wide, the eyes mischievous, the energy of a teenager trapped in a body that’s been through every battle rock ’n’ roll could throw at him. His bandmates Ben Marsden on guitar, “Random” Jon Poole on bass, and Charles Evans behind the kit were already buzzing like they’d been wound tight, waiting to explode. CJ strapped the colourful, fully ‘CJ’d Gibson ES335, on, this is not just any guitar, but a B.B. King signature Gibson Lucille, highly decorated, gleaming under the stage glare like a jewel.

He looked out across the crowd, beaming, his eyes darting across the room from under his pork pir hat, yelled a quick “evening Wolverhampton!” and then slammed straight into “Kick Down The Walls,” (from Split) the air crackling as the opening riff shook the Steel Mill to life. That first song, from his solo arsenal, born out of the ragged Wildhearts DNA that he’ll never quite escape, was everything you expected: hooks wrapped in distortion, a rhythm section pounding with punk urgency, CJ’s voice spitting venom one moment and melody the next.

And before the feedback had even died, the band lurched into “The Baddest Girl In The World,” (from Slots), the first of many cuts from his Robot era solo work, the jagged edges smoothed only by the sheer joy CJ seemed to take in thrashing it out. He was already leaping across the stage, springing into the air, splitting his legs into a madman’s version of cheerleader acrobatics, landing just in time to tear another riff out of Lucille. It wasn’t so much performance as chaos bottled and sprayed across the crowd, and the partisan faithful loved every moment.

Still riding the buzz, the band snapped into “Lemonade Girl,” a song that carried more of the melodic power-pop strain that CJ’s flirted with since his days in Honeycrack, where sugarcoated choruses sat atop guitars that still snarled and bit. Jon Poole’s bass bounced like a second voice, harmonising with CJ’s rasp, while Ben Marsden’s guitar lines wrapped around the main riff like barbed wire. That groove didn’t stop as “Go Away” burst out of the monitors, a stomper that had fists pumping and heads nodding in unison, the chorus screamed back at CJ by the faithful like they’d been rehearsing it in the rain outside.

He stepped to the mic between lines and, with a cheeky grin, mocked himself as “Errol Brown,” telling the room he’d been in so many bands over the years he’d lost count, before hurling himself back into the chorus as though proving that no matter where he’d been, this moment was where it all still mattered.

“Another Big Mistake,” (from Slots)rolled in without pause, thick with distortion, the rhythm section pounding a steady march while CJ spat out lines with half-snarl, half-smirk, the kind of song that feels like it could collapse in on itself at any second but holds together through sheer force of will. The sweat was already dripping off the stage, lights flashing red and white as “State of Us,” (from Seige) crashed in behind it, one of those cuts that feels like it was written to be screamed in a room like this, fast, furious, built for pogoing bodies, Charles Evans slamming the drums with all the subtlety of a demolition crew.

And just as the feedback was cutting into the room, “All the Rude Boys,” hit, its opening chords slashing like blades, CJ’s vocal more sneer than melody, the crowd soaking it up, a mosh pit opening and closing like a living organism in front of the stage.

The set had no patience for breathing room, and “Sitting at Home,” came in low and then rose, a song that showed off CJ’s knack for marrying The Wildhearts’ chaos with almost Beatles-esque hooks, Jon Poole’s basslines carrying it with a playful thump. CJ grinned through it, ducking and weaving, sweat flying, before throwing himself once more into the air for another cartoonish split that made the crowd roar louder than the amps. “Stormy in the North, Karma in the South,” a Wildhearts number, followed, dark, driving, full of tension, Lucille’s tone ringing thick and crunchy while Marsden doubled down with stabbing riffs, Evans pounding toms like tribal thunder.

And just when you thought the set might cool, it tore into “O.C.D.” another Wildhearts track was the finale, typically frantic and unrelenting, CJ spitting the words like a man possessed, the guitars shrieking, feedback screaming, the lights blinding in strobe bursts that turned the crowd into a blur of raised fists and wide eyes. As the last note hung in the air, CJ raised Lucille aloft like a prize-fighter’s belt, drenched in sweat, still smiling like a kid who’d just won a dare. The partisan crowd howled back their approval, knowing they’d been given a set that felt less like a warm-up and more like a fire alarm pulled at full tilt.

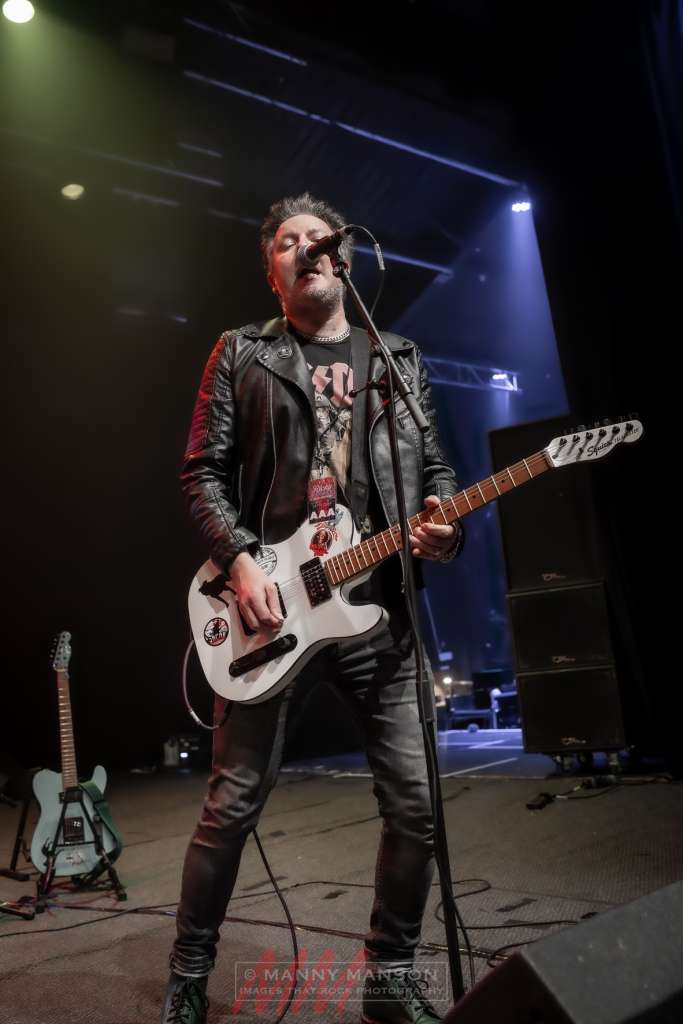

And then, as the smoke cleared and the stage reset, it was time for Ricky Warwick and the Fighting Hearts to turn the Steel Mill into their own battlefield. Warwick has lived a thousand lives — rising to fame with The Almighty in 1989 and dropping Blood, Fire & Love that same year, reinventing himself as a solo troubadour with albums like Tattoos & Alibis in 2003 and When Life Was Hard and Fast in 2021, then stepping into Phil Lynott’s shadow with Thin Lizzy and carving his own mark with Black Star Riders across four albums starting with All Hell Breaks Loose in 2013. He’s a man who’s carried the weight of rock history on his shoulders, but tonight, stripped back to himself and his Fighting Hearts, he looked like he was home — black guitar slung low, Belfast rasp ready, eyes glinting under the lights.

The band charged into “You’re My Rock ’n’ Roll,” from his 2015 solo record When Patsy Cline Was Crazy (and Guy Mitchell Sang the Blues), a statement of intent if ever there was one. The riff came down like a hammer, Ricky’s voice sandpaper raw, the chorus a call-to-arms, and the Steel Mill responded in kind, fists in the air, voices echoing back. Without letting the room breathe, they swung straight into “Wishing Your Life Away,” from the same album, its darker groove underpinned by a rolling rhythm section that drove the song like a runaway train. Warwick prowled the stage like a man who owned every inch of it, barking the verses with grit, then stepping back to let the chorus soar.

The crowd barely had time to exhale before “Are You Ready,” lifted from Black Star Riders’ All Hell Breaks Loose (2013), came roaring in, a song with Thin Lizzy blood in its veins, twin-guitar swagger and a stomp that felt like it had been written for nights exactly like this. The crowd bounced as one, Ricky grinning as if daring them to keep up, and then the band slid seamlessly into “Do You Understand,” a cut from Ricky’s passion project, The Almighty, its Celtic-tinged riff pulling the mood into storytelling territory, Ricky spitting lines like a street preacher over a wall of guitars.

Still riding that energy, the lights dropped into deep blue and “Angels of Desolation” emerged, from Blood Ties (2025), slower, heavier, drenched in menace. Ricky’s rasp turned almost to a growl, the Fighting Hearts stretching the sound thick and wide until it filled every corner of the Steel Mill. Then, without warning, the tempo picked up again with “Three Sides to Every Story,” from Tattoos & Alibis bouncing with an almost punk urgency, the chorus slamming into the crowd like a piledriver. Warwick strutted to the front, guitar raised, egging the crowd on, feeding on their energy.

“When Life Was Hard & Fast,” the title track of his 2021 solo album, landed like a confession set to power chords, a story of resilience and regret that the crowd sang like they’d lived it themselves. Warwick closed his eyes during the chorus, letting the words hit home, and then snapped back into the growling drive of “Don’t Leave Me in the Dark,” also from the new 2025 record, the lights flashing white across his sweat-streaked face as he barked the chorus.

“Another State of Grace,” title track of Black Star Riders’ 2019 album, hit next, all stomp and swagger, Thin Lizzy spirit laced with Ricky’s Belfast grit, the room singing along to the title line until the walls shook. And from there, the set only got harder, “Rise and Grind” (from Blood Ties) churning like a steam engine, Ricky spitting the verses with fire, before “Jonestown Mind,” the thunderous cut from The Almighty’s 1993 record Powertrippin’, dropped like a heavyweight punch. That riff rolled out, familiar and devastating, the crowd reacting like it had been waiting decades to scream it back.

The roof nearly came off when the band ripped into Thin Lizzy’s classic, “Jailbreak,” from the legendary 1976 album, a song Ricky has every right to sing after years carrying that torch. He snarled it with pride, not mimicry, and the Fighting Hearts made it their own, guitars slicing through the air, the crowd screaming “Tonight there’s gonna be a jailbreak!” so loud it could’ve been Dublin ’76 all over again. And as if that wasn’t enough, “Born to Lose” (by the Heartbreakers) carried the momentum forward, raw and ragged, before the darker stomp of “Celebrating Sinking” (also from Patsy Cline) bled into the room like an anthem for the broken.

The lights turned amber as “The Crickets Stayed in Clovis,” one of the highlights off the new album, unspooled like a sepia-tinged story, Ricky the storyteller more than frontman, his rasp tender, the band holding back just enough to let the narrative cut deep. But before the crowd could sink into reverie, “Schwaben Redoubt,” from Hearts on Trees, came snarling back, heavy, insistent, the band pounding it like a war drum.

From there it was a sprint to the finish. “Free ’n’ Easy,” the Almighty classic from Powertrippin’ (1993), blew the roof clean off, the crowd screaming it like their lives depended on it, the partisan energy boiling over as Warwick roared the lines with as much fury as he had thirty years ago. Straight after, “Finest Hour” (a Black Star Rider classic) surged in, an anthem of defiance and survival, Ricky clenching his fist as he sang, the band roaring behind him, lights flashing like a prize-fight, the crowd swaying like they were part of something far bigger than themselves. And then, finally, came “Fighting Heart,” the closer from When Life Was Hard and Fast, the perfect end to a night built on grit, resilience, and sheer rock ’n’ roll fire. Ricky poured every ounce of himself into it, his voice ragged but unbroken, his guitar raised in salute as the last chord rang out and the crowd howled their approval.

As the smoke thinned and the band left the stage, the Steel Mill was left ringing with feedback, sweat, and the echo of voices that weren’t ready to let go. CJ Wildheart had brought chaos, splits, and Lucille’s snarling scream; Ricky Warwick had brought storytelling, defiance, and a catalogue that spanned decades and bands but still felt urgent and alive. Together they’d turned a wet Wolverhampton Saturday into something unforgettable, a storm of riffs, lights, and heart that no amount of biblical rain could ever drown, even with animals running down the street two by two Jumanji style.